Yarnin’ Tariffs

Free trade is good. Negotiating to improve tariff rate asymmetries is fine. But seeking to erase trade balance asymmetry is mad yoke.

With all the sturm and drang over Trump’s Tariffs, what are we really talking about? Let’s start with the basics:

Econ 101: Trade Creates Wealth. If I have a sweater and you are cold, you have a bag of groceries and I am hungry, and we trade, we create wealth out of thin air. This is because each party is better off after the transaction than before. Equally? Rarely. But if both gain at all, there is reason to trade.

This is one of a short list of ideas with almost universal acceptance among economists, therefore, voluntary trade is a good thing and should be encouraged. Conversely, any friction between trades, like a tax on it (e.g., taking a sleeve of the sweater and 20% of the groceries), should be imposed sparingly, if at all, because it reduces the amount of potential wealth creation—unless the tax revenue is used for purposes worth more than the loss of wealth creation between traders. Of course, such redistribution always begs the problem of fairness: who gets what and who has the power to decide, but that’s for another yarn. Suffice it to say, tariffs are generally wealth-creation impediments, so be careful what you ask of Government.

Econ 101: Comparative Advantage. David Ricardo, an London stockbroker and economist, published in 1817 the concept of “comparative advantage” in his book “On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.” The idea, as true then as now, is that even if one party can do everything better, faster, and cheaper than another party, the superior producer should still not do everything itself if it wants to maximize wealth creation for itself—because of opportunity costs. In other words, even if one country pays another more for a product than it would cost to produce it itself, by not producing that product, labor and materials are freed-up to apply to far more valuable productive pursuits. Free trade writ large, therefore, can create even more wealth than from the simple sum of individual, voluntary transactions.

So, will Trump’s Tariffs impede wealth creation? Yes, because they will raise the cost of goods produced compared to free trading. More about this later.

How do tariffs work? The importer, not the exporter, pays a tariff to the U.S. Government, like a tax, based on the “landed value” of the product when it arrives at U.S. Customs. About this, therefore, Trump is wrong technically in claiming foreigners pay the tariffs. But substantively, he might be right if the cost of the tariff is shouldered by foreign exporters, or, otherwise put, if foreigners pay for the tariff in lower profit margins.

Who wins and who loses? Trade-wealth is diminished by tariffs, but tariff revenues can be used for other ends, like paying down the deficit or subsidizing American jobs. Is that a worthy trade-off? Often no, but a much tougher question.

Example. To help spin this yarn, let’s create a backdrop with a hypothetical example:

Assume Nike asks Nguyen Manufacturing in Da Nang to make a pair of Jordan Basketball shoes based on Nike’s design specifications (roughly half, I understand, of Nike footwear is currently made in Vietnam). Here is a hypothetical value chain:

1. Nguyen can manufacture the shoes for $20.00,

2. Nguyen charges Nike $25.00 ($20 plus a $5 profit), delivered to a Vietnamese port.

3. Nike pays $5.00 to ship the shoes from Vietnam to a Beaverton, Oregon warehouse,

4. Nike delivers the shoes to a Footlocker store, charging a wholesale price of $100.00

5. Footlocker sells the shoes retail for $200.

In this zero-tariff scenario, Nguyen has a profit margin of 20% ($5 profit/$25 sale), Nike has a gross margin of 70% ($70 profit/$100 sale), and Footlocker has a gross margin of 50.0% ($100 profit/$200 sale), all enabled by the end customer paying $200 for the shoes.

Now, POTUS imposes a 90% tariff on all goods from Vietnam. What happens?

Nike, as the importer, pays the tariff to U.S. Customs, based on the declared value or “landed cost” of the shoes when they arrive in the U.S. from Vietnam, thereby generating new revenues for the U.S. Government.

Nike’s landed cost for the shoes, in the hypothetical, totals $30.00 ($25.00 paid to Nguyen and $5.00 for shipping). The 90% tariff is therefore applied to the $30.00 landed cost, generating $27.00 in import tariff duties for the U.S. Government. And this is where the rhetorical, political mud gathers, determining who pays for the tariff.

If Nike has enough bargaining power, because it offers access to the almighty American consumer, it might be able to squeeze Nguyen Mfg to lower its price, in effect taxing the foreign company. Call that the scenario for Trump rhetorical license.

If, on the other hand, the $27.00 tariff is passed along by all parties to the retail purchaser of the shoes, the customer will pay a 13.5% higher price, or $227.00 instead of $200. So, this is the first bit of context to consider while holding your protest sign in the town center: A 90% tariff, in this example, translates into a 13.5% higher retail price. This is artificially manufactured inflation by tariff, of a significant amount, but it does not mean the customer pays 90% more for their shoes.

In addition, remember that tariffs only apply to imported goods, and the U.S. still produces roughly 50% of goods sold in the U.S., so U.S. consumers will not suffer a 13.5% increase on all products they purchase. And finally, Trump is levying different tariff rates against different countries, with 90% being the highest tariff on the hit list.

The Kit and Caboodle and Inflation. In 2024, the total value of imported goods and services was maybe $4 trillion. U.S. GDP in 2024 was about $27 trillion, with consumers accounting for roughly $18-$19 trillion. This means, crudely, that an across-the-board U.S. tariff on all imports will translate into much less than a dollar-for-dollar increase in our cost of living—because we still make around half of our own stuff and provide most of our own services.

So what would be the increase in our overall cost-of-living if, say, average, permanent tariffs of 20% were levied on the whole world? If the value-chain economics were similar for all imported goods as shown in the example above, and if imports account for roughly half of total consumer spending on goods, then, perhaps, overall goods prices for Americans could rise by 10% IF all tariffs are fully passed along in higher prices to consumers. Adding services to the mix, one might guess that overall prices for goods and services would rise by 2-3% or so if import tariffs were 20% across-the-board. That would be a shock to the cost of living but it not how the real-world works.

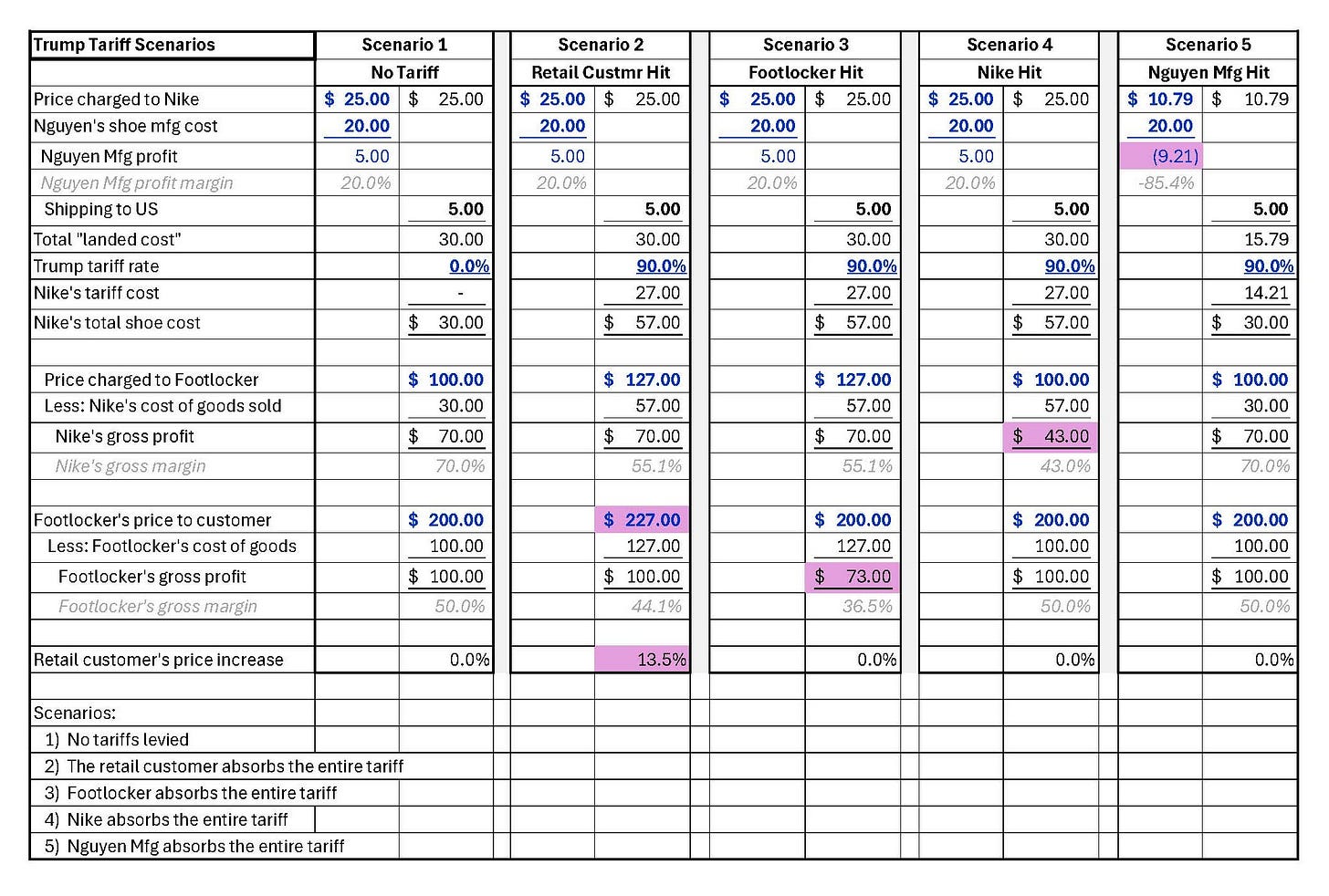

Let’s return to the hypothetical example, with several Nike/Vietnam scenarios:

What does this blur of numbers tell us? First, the chart shows that when tariffs are levied, it is unclear who exactly will suffer the burden and in what proportion. It is exceedingly unlikely, for example, that retail consumers will shoulder it all, because higher retail prices threaten unit sales, and therefore companies like Nike and Footlocker will be reluctant to raise prices by the full tariff. It is even less likely that the Vietnamese producer will eat the entire tariff (as Trump has claimed that foreigners pay the tariffs) because Nguyen would lose $9.21 on every pair it produces (Scenario 5).

So, what is the likely, overall impact of Trump’s tariffs? A mixture of pain distribution, of course, all along the value chain, ending in only a partial burden to the end-consumer and somewhat lower profitability to the companies.

What else do we notice from the chart? In Scenario 5 again, where Nguyen suffers the full impact of the tariff, the item’s price to Nike falls dramatically and the 90% tariff is applied to a far smaller, landed cost. But Nguyen won’t do that deal. So what if Nike buys Nguyen Manufacturing and runs it at a loss to suppress the landed value subject to tariffs? Customs authorities verify the declared value of imported goods through a structured process grounded in international agreements like the WTO Customs Valuation Agreement. If the buyer and seller are related, Customs assesses whether the relationship influences the landed cost. The declared value is then rejected if it deviates from market rates for identical or similar goods. Sounds simple, right? Far from it, with accounting allocations subject to many disputes between U.S. Customs and American importers. Imagine the bureaucracy costs required to keep the system honest, with millions of import entries per month. Whatever those costs, they come out of tariff revenues useable for the Federal budget.

More Mitigation. Besides the rest of the value chain taking some pain here and there to reduce the burden on the end consumer, what else might mitigate that consumer tariff burden via higher retail prices?

Price Elasticity. In the example, if Nike makes $70.00 per pair of Jordans now, and can still make $70 per pair after 90% tariffs by raising their prices to Footlocker (Scenario 3), they will likely sell fewer shoes to Footlocker for $127.00 than for $100.00. For 100,000 pairs marketable without tariffs, what if only 90,000 can be sold at a price 13.5% higher (e.g., a $227 post-tariff retail price/$200 non-tariff price)? In that case, Nike will make less in total profits even if they preserve their per-shoe gross profit. Nike will therefore consider the trade-off carefully and assume some of the burden.

Substitution Effect. When prices for one good suddenly rise, retail and commercial consumers find ways to substitute purchases with different but similar products and/or delay their purchases over time. The effect of both, in the example, is to reduce consumer demand for Jordans at higher prices by substituting or delaying purchases, which will either cost Footlocker sales or motivate them to reduce retail prices and accept lower profit margins. For products with more commodity-like profiles than Nike’s Jordans, American consumers will be quick to buy other products not subject to tariff-driven price increases. And this will mean, of course, domestic producers will benefit from a shift in spending away from imported goods. By buying non-Nike, domestic shoes, consumers will suffer no shoe inflation at all from tariffs, although some will complain of quality deflation.

Other Efficiencies. All companies impacted by tariffs will re-double efforts to cut other production and operating costs, to lessen the need to raise prices to preserve profits. This may be the least likely, material mitigator, because private companies, at all levels of the value chain, are always seeking to reduce costs anyway and therefore may already be operating at high levels of efficiency. But any improvement in efficiency can mitigate some of the eventual burden of tariffs on end-consumers.

These three mitigators of tariff pressure on retail prices will occur, to a greater and lesser degree, depending on the product, such that the odds are nearly zero of Scenario 2, where the customer must pay 13.5% more for Jordans. The customer might have to pay more than the original $200, but not $227.00.

Tariff Negotiations. None of the above assumes that Trump’s initial tariffs will engender tariff-rate reductions for US exports and the possibility, therefrom, of Trump backing down a bit on import tariffs. To wit, almost immediately after Trump’s 90% tariff announcement on Vietnamese products, Vietnam offered to reduce their own tariffs on American goods radically, to negotiate down the 90% US tariff. That would be a clear win for those in the Trump Administration who seek bilateral “fairness” in relative tariff rates, who see Trump’s plan as a one-time negotiating weapon to improve the U.S.’s trade landscape. But will it be percentage for percentage? Probably not, Trump being Trump, because Vietnam is far more dependent on American exports than the US is dependent on Vietnamese exports.

Onshoring and New Revenues. More worrisome is that for now, Peter Navarro seems to have the loudest voice in Trump’s ear and believes tariffs are not a negotiating weapon to achieve reciprocal rates but are intended to achieve reciprocal trade balances. The latter is a very different and largely impossible objective without shutting the U.S. off from the world entirely.

If the Navarro jihad prevails, the tariff endgame is really to generate new revenues for the Federal Government permanently and/or raise the price of foreign goods enough to motivate alternative, domestic production (“onshoring”). The latter will create American manufacturing jobs and, if you’re cynical, produce more Republican voters, which is not lost on the Democratic Party.

For example, if a U.S. shoemaker can make and sell Jordan’s to Nike for $50.00 a pair (twice what the Vietnamese shoe company would like to charge) because U.S. labor costs are so much higher—and there are no shipping or tariff costs—Nike will gladly switch to the domestic producer because the all-in equivalent cost of Vietnamese Jordans, including shipping and tariffs is $57.00. In this scenario, if the entire additional cost burden of domestic production is passed down to the American consumer, which it won’t, the retail price would need to rise to $220 from $200, or a 10% increase, instead of the worst case 13.5% due to tariffs on Vietnamese Jordans.

If you think about it, a 10%/$20 increase in price due to onshoring production (motivated by punitive tariffs on Vietnam) is effectively a subsidy for American manufacturers and workers, compared to free trade. Is a subsidy for American jobs (or robots) a good or bad thing all-in and is it worth higher prices to consumers? Andrew Yang, who has repeatedly warned of looming blue collar employment losses due Artificial Intelligence and Autonomous Driving, might argue that price-increase subsidies to prop-up American jobs might be better than extended unemployment insurance payments or revolution in the street. But we’d have to ask him.

Conclusion. Free trade is a good thing, for all. It creates wealth out of thin air and takes advantage of comparative advantage resource allocation. Free trade raises standards of living over protectionist, domestic-only policies. Tariffs, VATs and sales taxes, on the other hand, reduce wealth-creation potential, offset only if the tax revenues raised are spent for even more valuable purposes, such as motivating the onshoring of all manufacturing capability and capacity for our National Defense, or for reducing the budget deficit until we can get government spending under control.

If Trump’s Tariffs repair bilateral tariff-rate asymmetries; that is, motivate lower tariff rates imposed on American exports, American businesses and workers will be able to export more products to the world. And if by reducing tariffs on American exports, Trump then backs off on his import tariffs, American companies and workers will be helped by being able to import lower cost goods—and American consumers will suffer less inflation.

As a temporary negotiating weapon, I support Trump’s gambit, but if the real purpose is to create a permanently higher tariff regime to both raise Federal Government revenues and motivate higher-cost onshoring, that’s a yarn I don’t support. Permanent tariffs are bad, long-term economics compared to freer trade, unless, perhaps, it is paid-for by lowering income taxes. And that--consumption vs. income taxes—is a topic for another day.